Ureshino

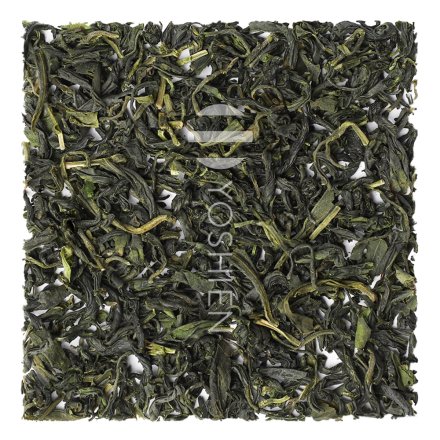

The cultivation region of Ureshino benefits from particularly fertile volcanic soil. Mr. Shigeki Ota's tea fields are located in a particularly natural and idyllic area and spread across 15 tea gardens ranging in 150-500m elevation. No pesticides or herbicides have been used at these gardens since 1978. The family has developed their own natural methods to protect the plants including the use of sugar, wood ash, and vinegar. Additionally, fertiliser is only used when absolutely necessary.

Kamairi

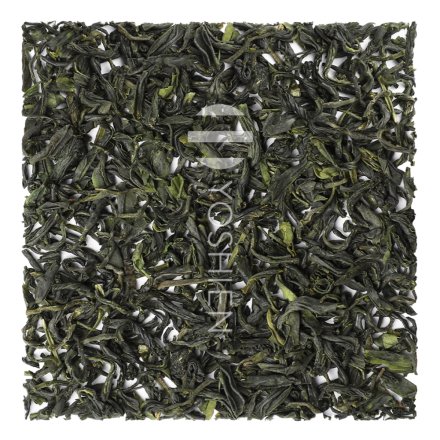

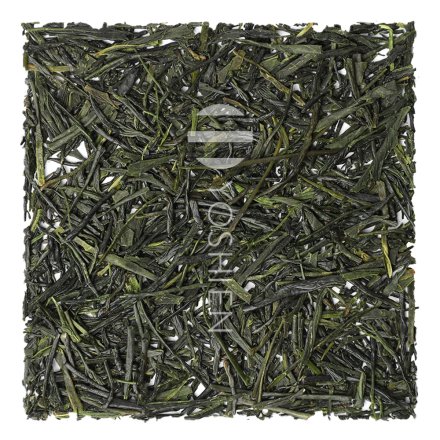

This variety is processed as kamairicha (釜炒り茶) (kama 釜, "kiln"; iri 炒り, "roast"; cha 茶, "tea"), which is made following a similar method to many Chinese green teas. Oxidation is prevented by firing the oven at around 105°C for 40 minutes. Kamairicha is rare in Japan, and only a few tea farmers specialise in the method.

Oven- or Pan-Firing

There are many different kamairi techniques. Historically, kamairi tea was rolled and fired by hand on a pan heated with quality wood for an even and long-lasting fire. In Miyazaki and Kumamoto (Aoyanagi technique), this method was carried out in a flat pan (hiragama) that could be used for roasting other products as well. By contrast, in Ureshino the tea was typically fired in a special pan at a 45° angle. Today, most kamairi teas are produced in metal ovens with gas or electric heating. The firing process is divided into an initial and brief stage at 300–400°C and finished in a second stage at 100°C.

China as a Common Origin: Kamairicha and Ceramics

The kamairicha technique was brought to Japan from China along with ceramics (produced using kilns). Potter Hong Lin Min (紅令民) brought the technique to Ureshino from China in 1504. Chinese tea seeds and the kamairi technique were brought to Reigan Temple by the Japanese monk Eirin Shyuzui as early as 1406. Since then, Kamairicha has become a traditional tea consumed in Kyushu. Tea farms in the northern highlands of Miyazaki have a reputation for being Japan's best Kamairi farms.

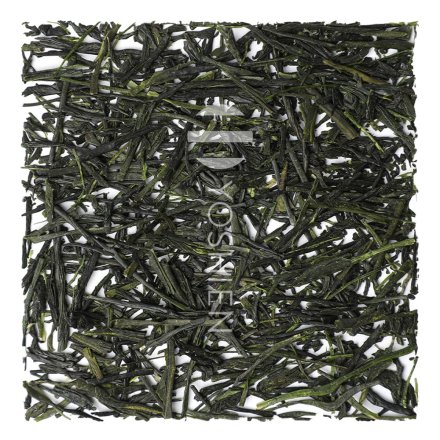

Kamairicha

Unlike steamed green teas, kiln-fired teas develop a unique, less bitter flavour with less astringency and a sweeter aftertaste. This is referred to as kamaka (釜香): kama (釜; pan/kettle), and ka (香; aroma). Kamairicha goes well with rich and salty foods, which are popular in Kyushu.